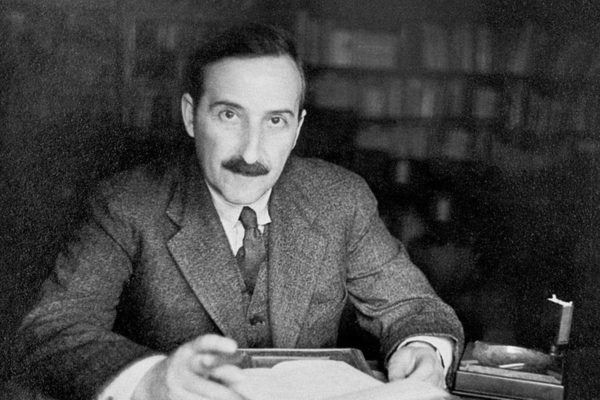

Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) fue un escritor austríaco. Nació el 28 de noviembre de 1881 en Viena, Austria.

En La Primera Guerra Mundial, Zweig debió presenciar el caos y la devastación de Europa. Fue testigo de la ascensión del nazismo en la década de 1930. Siendo de ascendencia judía y con una perspectiva humanista, Zweig se vio amenazado en su tierra natal. En 1934, decidió exiliarse y abandonó Austria, estableciéndose en Londres y luego en los Estados Unidos. Sus escritos contienen una profunda reflexión melancólica de la realidad bélica en Europa.

En 1942, Stefan Zweig y su esposa Lotte Altmann tomaron la decisión de suicidarse. Acto llevado a cabo en Petrópolis, Brasil.

El comienzo de Hitler

Es una ley de hierro de la historia que aquellos que se ven envueltos en los grandes movimientos que determinan el curso de su tiempo siempre fracasan en reconocerlos en sus etapas iniciales. Por lo tanto, no puedo recordar cuándo escuché por primera vez el nombre de Adolf Hitler, uno que durante años hemos estado obligados a mencionar o recordar en algún contexto todos los días, casi cada segundo. Es el nombre del hombre que ha traído más desgracia al mundo que cualquier otro en nuestro tiempo. Sin embargo, debo haberlo escuchado bastante temprano, porque Salzburgo podría describirse como un vecino cercano de Múnich, a solo dos horas y media de viaje en tren, por lo que pronto nos familiarizamos con sus asuntos puramente locales. Todo lo que sé es que un día, no puedo recordar la fecha exacta, un conocido de Múnich que nos visitaba se quejó de que había problemas allí nuevamente. En particular, dijo, un agitador violento llamado Hitler estaba celebrando reuniones que se convertían en peleas salvajes, y estaba abusando de la República y avivando sentimientos antisemitas en un lenguaje muy vulgar.

El nombre no significaba nada en particular para mí, y no pensé más en ello. En el inseguro estado alemán de la época, los nombres de muchos agitadores que llamaban a un putsch seguían surgiendo, solo para desaparecer rápidamente de la atención pública, y ahora están completamente olvidados. Estaba el Capitán Ehrhardt con su Brigada Báltica, estaba Wolfgang Kapp, estaban los asesinos de la Vehm, los comunistas bávaros, los separatistas del Rin, los líderes de las diversas bandas conocidas como Freikorps. Cientos de estas pequeñas burbujas de descontento flotaban en la fermentación general de la época, dejando atrás solo un mal olor que mostraba claramente cómo las heridas aún abiertas de Alemania estaban supurando y pudriéndose. En algún momento, el boletín de la nueva corriente Nacional Socialista estuvo entre los que llegaron a mis manos. Era el Miesbacher Anzeiger, que luego se convirtió en el Völkischer Beobachter. Pero Miesbach era solo un pequeño pueblo, y el boletín estaba muy mal escrito. ¿Quién se molestaría con ese tipo de cosas?

Sin embargo, de repente aparecieron bandas de jóvenes en las ciudades fronterizas vecinas de Reichenhall y Berchtesgaden, lugares que visitaba casi todas las semanas. Estas pandillas eran pequeñas al principio, y luego crecieron más y más. Los jóvenes llevaban botas altas y camisas marrones, y cada uno lucía un brazalete de colores chillones con una esvástica. Marchaban y celebraban reuniones, desfilaban por las calles, cantaban canciones y coreaban en coro, pegaban carteles enormes y ensuciaban las paredes con esvásticas. Por primera vez, me di cuenta de que debían de haber fuerzas financieras y otras influyentes detrás de la aparición repentina de estas pandillas. Hitler seguía dando sus discursos exclusivamente en bodegas de cerveza bávaras en ese momento, y él solo no podría haber equipado a estos miles de jóvenes con un equipo tan costoso. Manos más fuertes debían estar ayudando a impulsar el nuevo movimiento hacia adelante. Pues los uniformes estaban impecablemente limpios y ordenados, y en un momento de pobreza cuando los auténticos veteranos del ejército aún andaban con sus desgastados uniformes, los ‘tropas de asalto’ enviados de ciudad en ciudad y de ciudad en ciudad podían disponer de una sorprendentemente amplia flota de coches, motocicletas y camiones nuevos para transportarse. También era obvio que estos jóvenes estaban recibiendo entrenamiento táctico de líderes militares, estaban siendo adiestrados, de hecho, como paramilitares, y también que el ejército alemán regular en sí mismo, la Reichswehr, para el cual Hitler había actuado como espía, proporcionaba instrucción técnica regular en el uso de equipo que le suministraban fácilmente. Sucedió que tuve la oportunidad de presenciar uno de estos ejercicios de entrenamiento militar. Cuatro camiones rugieron de repente en uno de los pueblos fronterizos donde se estaba celebrando una reunión perfectamente pacífica de los socialdemócratas. Todos los camiones estaban llenos de jóvenes nazis armados con porras de goma, y abrumaron la reunión, que no los esperaba, por pura rapidez. Había visto exactamente lo mismo en la Piazza San Marco en Venecia. Era un método que habían aprendido de los fascistas, pero lo ejecutaban con mucha mayor precisión militar, llevándolo a cabo sistemáticamente hasta el último detalle, como cabría esperar de los alemanes. Un silbato dio la señal, y los hombres de las SA saltaron rápidamente de sus camiones, golpeando con porras de goma a cualquiera que se interpusiera en su camino. Antes de que la policía pudiera intervenir, o los trabajadores de la reunión pudieran agruparse, habían saltado de nuevo a los camiones y se alejaban a toda velocidad. Lo que me sorprendió fue la manera práctica en que saltaron de los vehículos y volvieron a subir, ambas veces siguiendo una única y fuerte señal de silbato de su líder. Se podía ver que los músculos y nervios de cada uno de estos jóvenes habían sido entrenados previamente, de modo que sabía cómo moverse y sobre qué rueda del vehículo debía saltar para no interponerse en el camino del hombre detrás de él y así poner en peligro toda la maniobra. No se trataba de habilidades personales. Cada uno de esos movimientos debía haberse practicado previamente, docenas o incluso cientos de veces, en cuarteles y campos de desfile. Desde el principio, como cualquiera podría ver de un vistazo, esta pandilla había sido entrenada en métodos de ataque, violencia y terrorismo.

INCIPIT HITLER

IT IS AN IRON LAW OF HISTORY that those who will be caught up in the great movements determining the course of their own times always fail to recognise them in their early stages. So I cannot remember when I first heard the name of Adolf Hitler, one that for years now we have been bound to speak or call to mind in some connection every day, almost every second. It is the name of the man who has brought more misfortune on the world than anyone else in our time. However, I must have heard it quite early, because Salzburg could be described as a near neighbour of Munich, only two-and-a-half hours’ journey away by rail, so that we soon became familiar with its purely local affairs. All I know is that one day—I can’t now recollect the exact date—an acquaintance from Munich who was visiting us complained that there was trouble there again. In particular, he said, a violent agitator by the name of Hitler was holding meetings that became wild brawls, and was abusing the Republic and stirring up anti-Jewish feeling in very vulgar language.

The name meant nothing in particular to me, and I thought no more about it. In the insecure German state of the time, the names of many agitators calling for a putsch kept emerging, only to disappear quickly from public attention, and they are now long forgotten. There was Captain Ehrhardt with his Baltic Brigade, there was Wolfgang Kapp, there were the Vehmic murderers, the Bavarian Communists, the Rhineland separatists, the leaders of the various bands known as Freikorps.2 Hundreds of these little bubbles of discontent were bobbing about in the general fermentation of the time, leaving nothing behind when they burst but a bad smell which clearly showed how Germany’s still open wounds were festering and rotting. At some point the newsletter of the new National Socialist movement was among those that came into my hands. It was the Miesbacher Anzeiger, later to become the Völkischer Beobachter.3 But Miesbach was only a little village, and the newsletter was very badly written. Who would bother with that kind of thing?

Then, however, bands of young men suddenly turned up in the neighbouring border towns of Reichenhall and Berchtesgaden, places that I visited almost every week. These gangs were small at first, and then grew larger and larger. The young men wore jackboots and brown shirts, and each sported a garishly coloured armband with a swastika on it. They marched and held meetings, they paraded through the streets, singing songs and chanting in chorus, they stuck up huge posters and defaced the walls with swastikas. For the first time, I realised that there must be financial and other influential forces behind the sudden appearance of these gangs. Hitler was still delivering his speeches exclusively in Bavarian beer cellars at the time, and he alone could not have fitted out these thousands of young men with such expensive equipment. Stronger hands must be helping to propel the new movement forwards. For the uniforms were sparkling neat and clean, and in a time of poverty when genuine army veterans were still going around in their shabby old uniforms, the ‘storm troops’ sent from town to town and city to city could draw on a remarkably large pool of brand new cars, motorbikes and trucks for transport. It was also obvious that these young men were getting tactical training from military leaders—were being drilled, in fact, as paramilitaries—and also that the regular German army itself, the Reichswehr, for whose secret service Hitler had acted as a spy, was providing regular technical instruction in the use of equipment readily supplied to it. It so happened that I had an opportunity of observing one of these combat training exercises. Four trucks suddenly roared into one of the border villages where a perfectly peaceful meeting of Social Democrats was being held. All the trucks were full of young National Socialists armed with rubber truncheons, and they overwhelmed the meeting, which was not expecting them, by dint of sheer speed. I had seen just the same thing in the Piazza San Marco in Venice. It was a method they had learnt from the Fascists, but they executed it with much greater military precision, systematically carrying it out down to the last detail, as you might expect of the Germans. A whistle gave the signal, and the SA4 men jumped swiftly out of their trucks, bringing rubber truncheons down on anyone who got in their way. Before the police could intervene, or the workers at the meeting could group together, they had jumped back into the trucks and were racing away. What surprised me was the practised way in which they jumped out of the vehicles and back in again, both times following a single sharp whistle signal from their leader. You could see that the muscles and nerves of every one of these young men had been trained in advance, so that he knew how to move and over which wheel of the vehicle he must jump out to avoid getting in the way of the man behind him and thus endangering the whole manoeuvre. It was not a matter of personal skills. Each of those movements had had to be practised in advance, dozens or even hundreds of times, in barracks and on parade grounds. From the first, as anyone could see at a glance, this gang had been trained in methods of attack, violence and terrorism.

Extraído de STEFAN ZWEIG. The World of Yesterday. Pushkin Press. 2009.